1809 Treaty of Fort Wayne

Treaty Between the United States and the Delaware, Potawatomi, Miami and Eel River Indians at Fort Wayne, September 30,...

Posted by Today's Document on Monday, September 30, 2024Monday, September 30, 2024 post by Today's Document on Facebook:

Treaty Between the United States and the Delaware, Potawatomi, Miami and Eel River Indians at Fort Wayne, September 30, 1809

Record Group 11: General Records of the United States GovernmentSeries: Indian TreatiesFile Unit: Ratified Indian Treaty 57: Delaware, Potawatomi, Miami, and Eel River - Fort Wayne, September 30, 1809

James Madison, President of the United States of America.

To all and singular, to whom these present shall come, Greeting.

Whereas a certain Treaty between the United States and the Delaware, Putwatime, Miami and Ell River Tribes of Indians was concluded and signed at Fort Wayne on the 30th day of September last past, which Treaty is as follows:

A Treaty Between the United States of America and the Tribes of Indians called the Delawares, Patawatimies, Miamies & Eel River Miamies

James Madison President of the United States by William Henry Harrison Governor and comander in Chief of the Indiana Territory superintendent of Indian affairs and commissioner plenipotentiary of the United States for Treating with the same Indian Tribes & the Sachems Head men & Warriors of the Delware Putawatime Miami & Eel Rive Tribes of Indians have agreed and concluded upon the following Treaty which when ratified by the said President with the advice & consent of of the Senate of the United States shall be binding on said parties

Article 1st. The Miami & Eel River Tribes & the Delewares & Potawatimees as their allies agree to cede to the United States all that Tract of Country which shall be included between the boundary line established by the Treat of Fort Wayne the Wabash and a line to be drawn from the mouth of a creek called Racoon Creek emptying into the Wabash on the South east side about twelve miles below the mouth of the Vermillion River so as to strike the boundary line established by the Treaty of Grouseland at such a distance from its commencement at the north east corner of the Vincennes Tract, as will leave the Tract now ceded thirty miles wide at the narrowest place, And also all that Tract which shall be included between the following boundaries Vizo beginning at Fort Recovery thence southwardly along the General boundary line established by the Treaty of Greenville to its intersection with the boundary line established by the Treaty of Grouseland thence along said line to a point from which a line drawn parallel to the first mentioned line will be twelve miles distant from the same & along the said parrallel line to its intersection with a line to be drawn from fort Recovery parallel to the line esta- blished by the said Treaty of Grouseland

Article 2 The Miamies explicitly acknowledge the equal right of the Delewares with themselves to the Country Watered by the White River, But it is also to be clearly understood that neither party shall have to right of disposing of the same without the consent of the other, And any improvements which shall be made on the said land by the Delewares or their Friends the Mochecans shall be theirs forever

Article 3 The compensation to be given for the cession made in the first article shall be as follows Vizo To the Delewares a permanent annuity of five hundred Dollars, To the Miamies a like annuity of five hundred Dollars, to the Eel River Tribe a like annuity of two hundred and fifty Dollars, And to the Putawatomies a like annuity of five hundred Dollars

Article 4 All the stipulations made in the Treaty of Greenville relatively to the manner of paying the annuities and the right of the Indians to hunt upon the land shall apply to the annuities granted and the land ceded by the present Treaty.

Article 5 The consent of the Wea Tribe shall be necessary to complete the title to the first Tract of land here ceded a Seperate convention shall be entered into between them & the United States and a reasonable allowance of Goods given them in hand and a permanent annuity which shall not be less than three hundred Dollars Settled upon them

Article 6 The annuities promised by the third article & the Goods now delivered to the amount of five Thousand two hundred Dollars shall be considered as a full compensation for the cession made in the first article

Article 7 The Tribes who are parties to this Treaty being desirous of putting an end to the depredations which are committed by abandoned individuals of their own color upon the Cattle Horses & of the more Industrious & careful, agree to adopt the following regulations Viz. When any theft or other depredation shall be committed by any individual or individuals of one of the Tribes above mentioned upon the property of any individual or individuals of an other Tribe the Chiefs of the party injured shall make application to the agent of the United States who is charged with the delivery of the Annuities of the Tribe to which the offending party belongs whose duty it shall be to hear the proofs & allegations on other side and determine between themes And the amount of his award shall be immediately deducted from the Annuity of the Tribe to which the offending party belongs & given to the person injured on the Chief of his Village for his use

Article 8 The United States agree to relinquish their right to the reser[illegible - reservation?] the old Ouiatenon Town made by the Treaty of Greenville so [illegible] least as to make no further use of it than for the establishment of a military Post Articles 9th The Tribes who are parties to the Treaty being desirous to shew their attachment to their brothers the Kickapooz agree to cede to the United States the land on the north west side of the Wabash from the Vincennes Tract to a northwardly extension of the line running from the mouth of the aforesaid Raccoon Creek and fifteen miles from one width the Wabash, on condition that the United States shall allow them an annuity of four hundred Dollars But this article is to have no effect unless the Kickapooz will agree to it

In Testimony whereof the said William Henry Harrison & the Sachens & War Chiefs of the before mentioned Tribes have hereunto set their hands and affixed their Seals at Fort Wayne this 30th of September 1809

[signed] William Henry Harrison

[column 1]

Delawares:

Anderson, for Hockingpomskon, who is absent x [seal]

Anderson x [seal]

Petchekekapon x [seal]

The Beaver x [seal]

Captain Killbuck x [seal]In presence of

[signed] Peter Jones, secretary to the Commissioner

[signed] John Johnson, Indian agent

[signed] A. Heald, Capt. U. S. Army

[signed] A. Edwards, surgeon's mate

[signed] Ph. Ostrander, Lieut. U. S. Army

[signed] John Shaw

[signed] Stephen Johnston

[signed] J. Hamilton, sheriff of Dearborn County

[signed] Hendrick Aupaumut

[signed] William Wells }

[signed] John Conner } Sworn Intepreters

[signed] Joseph Barron }

[signed] Abraham Ash }

[column 2]

Pattawatimas:

Winemac x [seal]

Five Medals, by his son x [seal]

Mogawgo x [seal]

Shissahecon, for himself and his brother Tuthinipee x [seal]

Ossmeet, brother to Five Medals x [seal]

Nanousekah, Penamo's son x [seal]

Mosser x [seal] Chequinimo x [seal]

Sackanackshut x [seal]

Conengee x [seal][column 3]

Miamis:

Pucan x [seal]

The Owl x [seal]

Meshekenoghqua, or the Little Turtle x [seal]

Wapemangua, or the Loon x [seal]

Silver Heels x [seal]

Shawapenomo x [seal]Eel Rivers:

William Henry Harrison at Upper Piqua during the War of 1812: Ref. William Henry Harrison, His Life and Times, James A....

Posted by Johnston Farm & Indian Agency on Monday, September 30, 2024Monday, September 30, 2024 post by Johnston Farm & Indian Agency on Facebook:

William Henry Harrison at Upper Piqua during the War of 1812: Ref. William Henry Harrison, His Life and Times, James A. Green, 1941 Garrett and Massie

That treaty (author’s note: Fort Wayne treaty) was made in the summer of 1809. In the following year 1,779 Indians came to Fort Wayne to be present at the distribution of the annuities. John Johnson (sic) the agent, a man of pure integrity, wrote to Governor Harrison that they “went home perfectly satisfied,” and for ten months after the treaty “not a lisp of discontent was heard from any of those who were parties to it,” so the governor said in his annual message to the Legislature in November, 1810. p.119

- Journal of the proceedings: Indian treaty, Fort Wayne, September 30th, 1809 [read online] at CurateND University of Notre Dame.

- Barce, E. (1915). Governor Harrison and the Treaty of Fort Wayne, 1809. Indiana Magazine of History. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/imh/article/view/5951 Issue Volume 11, Issue 4, December 1915 at Indiana Magazine of History journal in the archives at Indiana University Scholarworks. Read online at JSTOR.

- Barce, E. (1916). Tecumseh’s Confederacy. Indiana Magazine of History. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/imh/article/view/5972 Issue Volume 12, Issue 2, June 1916 at Indiana Magazine of History journal in the archives at Indiana University Scholarworks. Read online at JSTOR.

- Treaty of Fort Wayne document from INDIAN- AFFAIRS. LAWS AN-D TREATIES. V,:-1. II. (TREATIES.) COMPILED AND EDITED .,BY CHARLES J. KAPPLER, LL. M., CLERK TO THE SENATE COMMITTEE ON INDIAN AFFAIRS. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1904. at the National Museum of the American Indian at the Smithsonian Institute.

- 1809: Treaty of Fort Wayne takes 3 million acres from Native peoples at Native Voices National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health.

- Treaty with the Delawares etc 1809 at Indiana Documents Leading to Statehood at Indiana Historical Bureau.

- The Treaty of Fort Wayne, 1809—a treaty that led to war—goes on exhibit

In 1809, nearly 1,400 Potawatomi, Delaware, Miami, and Eel River Indians and their allies witnessed the Treaty of Fort Wayne, ceding 2.5 million acres of tribal lands in present-day Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio in exchange for a peace that did not last. This September, representatives of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi saw the treaty go on view at the National Museum of the American Indian. “It is an honor to come full circle to an article that our ancestors signed,” Tribal Chairman John P. Warren said. “I hope we are fulfilling their hopes and dreams by being here.”

Dennis Zotigh September 29th, 2017. NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIANSMITHSONIAN VOICESfrom the Smithsonian Museums in Smithsonian Magazine. -

December 13, 2021 post by Military History of Fort Wayne on Facebook:

THE TREATY OF FORT WAYNE

In 1809, at the military installation of Fort Wayne, the United States negotiated a treaty with "chiefs" of various tribes including the Miami and Potawatomi to transfer approximately 3 million acres of land to the United States. The actual authority of these chiefs is much in question as many seem to have been self-appointed or even US Government appointed chiefs carrying little authority with the tribes they represented.

Officially this treaty is known as the Fort Wayne Treaty but unofficially it is known as the Whiskey Treaty as the natives were plied with whiskey in order to coerce their signatures to the treaty.

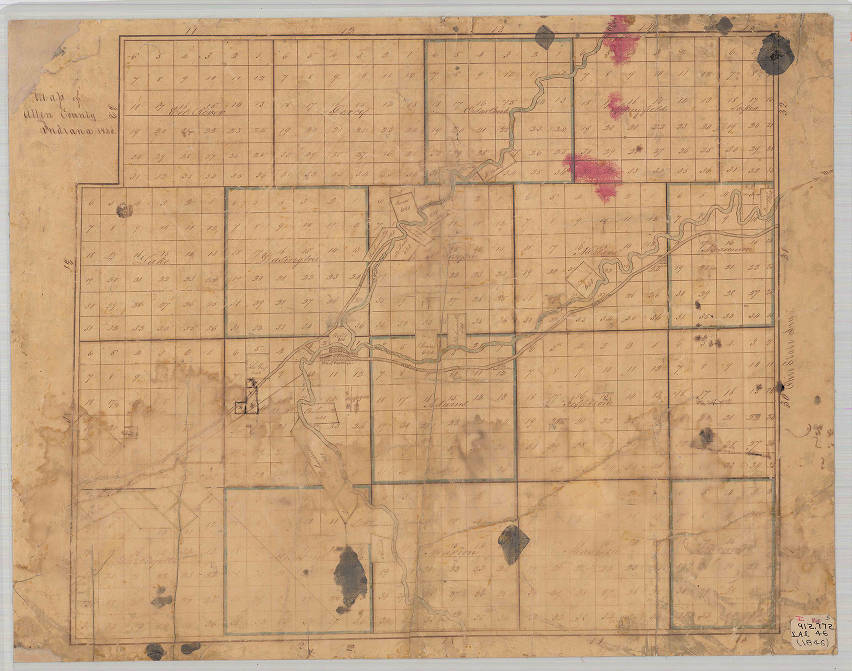

News of this meeting is received angrily by natives who were not present as it is their land that has been signed away by treaty without their approval. The map attached illustrates the various Indian Reservations of Allen County, Indiana as they still existed for the later treaties of October 1818 and October 1826.

WILLIAM WELLS AND THE MIAMI INDIANS

It's difficult to do Wells any justice in a few sentences but he was a larger-than-life character who had been captured by Miami in Kentucky as a young boy and was adopted into the Miami tribe, eventually becoming a Miami warrior.

Wells must have been an intimidating sight as a battle-painted warrior with bright red hair, pale skin with his tomahawk in one hand and a scalping knife in the other. Unfortunately for many Americans, this was the last sight they would ever see. He fought against the Americans at a battle known as St. Clair's Defeat on November 4, 1791 – in defense of the Miami homelands. Wells is said to have swung his tomahawk that day until he could barely lift his arms. The American casualty rate at St Clair’s Defeat was nearly 98% and fully one-quarter of the entire US Army was wiped out on that day. The battlefield is largely intact and can still be visited today at Fort Recovery, Ohio.

Wells later switched sides to become a scout for Anthony Wayne for his 1794 campaign against the Northwest Indians. At the Treaty of Greenville, Wells was given a large tract of land near Fort Wayne as a preemption for his service. Captain Wells would then serve as an Indian Agent at Fort Wayne for several years. Wells could speak many native languages, and mainly treated the natives fairly although he was not completely trusted by either side due to his history of divided allegiances.

WILLIAM WELLS’ PREEMPTION (RESERVATION)

Near downtown Fort Wayne reservation #12 (map enclosed) was the preemption for Captain William Wells. It is from Wells and his preemption from which we draw the name Wells Street and Spy Run Avenue.

Wells' home was on his preemption, and he occupied a two-story log cabin at what is today at the rear of 1410 Spy Run Avenue in Fort Wayne. Wells was the son-in-law of Chief Little Turtle who died in July 1812. Little Turtle was interred at a small burial ground which was lost to history and unknown until 1912 when his grave was again discovered during construction of what is today 634 Lawton Place in Fort Wayne. Among his effects was a sword gifted him by George Washington – currently preserved at the Allen County History Center.

THE WAR OF 1812 COMES TO FORT WAYNE

In an 1810 meeting at Vincennes, an enraged Shawnee Chief Tecumseh tells future-President and then Indiana Territory Governor, William Henry Harrison in a speech that, "11 debt-ridden, whiskey-soaked ’treaty chiefs’ do not have the authority to sign agreements for lands they do not own or have authority over.”

Tecumseh insisted that the Treaty of Fort Wayne be rescinded, and Harrison and Tecumseh almost come to blows. This will directly lead to a war between Tecumseh's Confederacy (supported by the British) and the United States and intersect with the War of 1812. Tecumseh, in concert with the British, led attacks on US installations along the frontier. On July 18, 1812, British and native Warriors take control of Fort Mackinaw. When word reaches Wells in Fort Wayne, he feared for the installation at Fort Dearborn at modern-day Chicago.

FORT DEARBORN CHICAGO – A PRELUDE TO THE SIEGE OF FORT WAYNE

William Wells quickly assembled a relief of 30 Miami warriors to march from Fort Wayne and support Fort Dearborn. Wells is seen as a traitor by the Potawatomi and is killed on August 15, 1812 while escorting evacuees from Fort Dearborn for Fort Wayne. Various accounts of his death agree that he was shot and pinned under his horse. From there the versions vary as to what happened next – whether kind words or insults were exchanged – but eventually he is killed, and some gruesome accounts say that his heart was cut from his chest and devoured by his enemies. Wells remains are interred at the Massacre site to this day.

After the Siege of Fort Mackinaw and Fort Dearborn, one of the next installations to be attacked is Fort Wayne itself.

THE SIEGE OF FORT WAYNE

From September 5-12, 1812, approximately 500 warriors led by Winamac and Five Medals would lay siege to the Fort Wayne’s Garrison of approximately 100 men. Fort Commander, Captain James Rhea, immediately sent letters to ask for reinforcement.

A relief force of 3,000 under William Henry Harrison, marched from Newport, Kentucky. Captain Rhea is able to get news that a reinforcement is in route and continues to hold the fort. On September 12th, knowing a relief force is approaching, Winamac is forced to break off his siege of Fort Wayne and retreat.

The War with Tecumseh continued until 1813 when Tecumseh is eventually killed in Canada, and his Confederacy defeated.

THE REMOVAL OF REMAINING NATIVES FROM THE REGION

In 1820 Andrew Jackson was elected President and his administration did not believe native and white populations could live side-by-side peacefully. In 1823, at a treaty in St Mary's, Ohio it was designated that all the native populations would be removed to reservations in the west by August 1, 1844.

The most notable removal effort was in 1838 when Governor Wallace appointed General John Tipton to round up the natives and remove them to a reservation in Kansas in what is today referred to as the Trail of Death. The trail of death was a forced march of some 600 miles and a two-month trek during December and January, to Kansas. 42 died – half of them children –in route.

This was the same year in which the Cherokee were forced on the Trail of Tears from North Carolina to Oklahoma.

Forcible removals continued in Indiana until 1846 when remaining natives were hunted down, their homes and villages burned and the last taken west.